The Secrets of Roman Numerals

January Latin Challenge: Day 18

We’re past the midway point in the January Latin Challenge! Well done for keeping up with it!

As a little break, our rest day from Latin grammar, we are going to look at the world of Roman Numerals. Specifically, how the Romans REALLY wrote their numbers.

Before we start I want to give you my free guide: 3 Simple Steps to Instantly Improve Your Latin Translation. It has some easy tips for instantly helping you become more accurate in your translations of Latin sentences and passages.

Still Relevant

Roman Numerals are the sort of thing everyone thinks they should know, and that’s mainly because people still use them today. You see them used on all sorts of buildings, companies, and events. However, lots of people struggle to remember the rules for how numerals work, so I am going to go through these today.

Numerals are actually very straightforward when you break them down, so let’s go straight to the basics. The 3 most important numerals (letters) to remember are:

I = 1

V = 5

X = 10.

For all the numbers in between, you use a combination of these letters. For example,

2 is II. (1 + 1)

3 is III. (1 + 1 + 1)

Here it gets trickier:

for 4, don’t use IIII, although that fits the pattern.

Instead take the letter for 5, V, and we minus 1, I.

To do this, we have to put the I before the V, so its one less than 5, which is 4.

IV = 4

The same principle applies for the next few numbers:

VI = 6

VII = 7

VIII = 8

For 9, don’t cram 4 ‘I’s on the end of the V. Instead, take X (10) and minus 1 from it.

IX = 9 (one fewer than 10)

Bigger Numbers

For the teens, do exactly the same as 1-10 - just add an X at the start. So:

XI = 11,

XV = 15,

XX = 20.

How would you write these numbers in Latin?

14

16

19

Keep reading when you have figured it out!

14 would be X and 1 less than V, so you write that as XIV.

16 therefore would be XVI,

19 would be XIX.

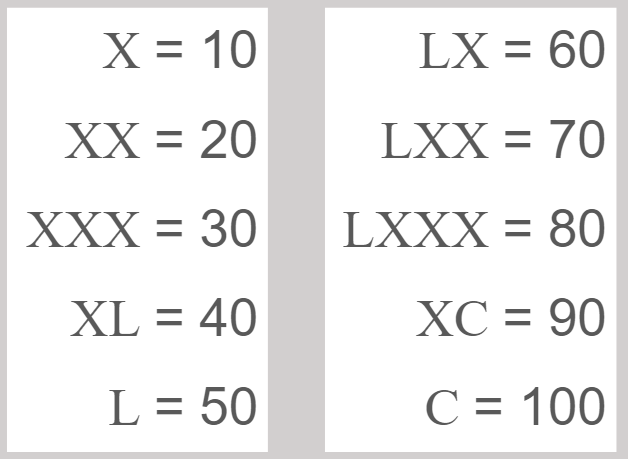

Here is how to write all the 10s in Roman numerals. Take a second to look them over.

Also, some higher numbers that are especially useful for dates on buildings.

D is 500, M is 1000

So when was this building built?

M = 1000,

DCCC = 800, so 1800 all together so far.

Then LXXX for 80

Finally IV for 4.

1884.

The big secret

Now for the secret to Roman numerals. Romans did not always stick to these rules. You will often see, for example, the number 4 on our clocks today. We would expect IV, but some clocks use IIII.

The colosseum uses this notation invariably for entrance numbers containing the digit 4, but oddly does contract most other numbers, like 40 (XL). Similarly, you can see 90 shown as XC or as LXXXX.

There are various theories about why some writers used the longer forms of the numbers, and not what is called the subtractive method of notation (where you show something as one, or 10, or 100 fewer than the next large number).

Mathematical errors?

Some people say it is due to errors that would occur in maths if the subtractive method was used, due to the Roman way of addition - bring the numerals into order greatest to least for the answer.

For example, 5 + 15 is easy, X+V+V is 10.

But 19+27 is more difficult:

XIX+XXVII would become X+X+X+X+V+I+I+I, which would give the answer 48, rather than 46!

Perhaps the longer form of 19 would be helpful here, to avoid the errors of using the subtractive notation.

Saving Space

However, the main reason we see the subtractive method most often is because we are usually looking at carvings. Details of numbers about legions or people or whatever have mainly survived in inscriptions, and the main issue with carving into stone is space! You want to use the least amount of space possible for your message, because a larger message means a larger, more expensive block of stone!

A stone carver isn’t going to spend time (and money) carving MDCCCCLXXXXIIII into a block, if MCMXCIV will do the trick.

Secrets exposed, mission accomplished

I hope you have enjoyed this post, and that you have found it useful! Thanks so much for reading, and I’ll see you tomorrow for Day 19 of the bambasbat January Latin Challenge!